Note 30: Alas! Poor Kraken!

What to do when your Sea Monster ends up being a Sea Monkey...

I was a very good boy this week.

Despite the barrage of comments (public and private) from folks that Sidney Powell was going to show how Trump actually won the election with her Kraken Lawsuit, I didn’t dunk on anyone once, and kept my uncontrollable chortling all to myself.

If you’re not following along, after being sued by voting machine vendors for defamation around her comments between the election and Biden assuming the presidency, poor Sidney is trying to bring back the ‘90s “NOT!”:

Former Trump campaign lawyer Sidney Powell yesterday responded to the $1.3 billion defamation lawsuit that Dominion Voting Systems filed after she repeatedly accused the company of participating in an elaborate international conspiracy to deny Donald Trump his rightful victory in last year's presidential election. Her defense, more or less, is that she did not really mean what she said.

True, Powell claimed over and over again that Dominion rigged voting machines to manufacture "millions" of votes for Joe Biden. She fingered a specific Dominion executive as largely responsible for the scheme, claimed the plot had its roots in fraud-facilitating software that had helped keep Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chavez in power, and said China, Cuba, and George Soros were also in on it. But "no reasonable person would conclude that the statements were truly statements of fact," Powell says in her motion to dismiss the lawsuit.

Powell thus implies that Trump and the millions of supporters who still believe he actually won the election, thanks in no small part to the fantasy she concocted, do not count as reasonable people. Fair enough, I suppose, although one might question the wisdom of throwing them all under the bus if Powell hopes to continue profiting from their credulity. But why does Powell purport to be surprised by the fact that so many Trump followers believed her?

As much as I would like to store this arrow in my quiver of arguments to shoot back at the same folks who will be peddling some other form of insanity in the future, I expect that while former Powell fans will hold onto the belief that the election was stolen, their keystone argument that relied on the integrity and competence of Esquire Sidney will be memory-holed pretty quickly alongside their beliefs in Obama birtherism, Operation: Jade Helm, and the idea that COVID is less dangerous than the common flu.

Real Talk™ on Voting

Now that Biden has signed the American Rescue Plan into law (a welcome departure from executive orders), attention these days is focused on H.R.1, a.k.a the For the People Act. Before we jump into the contents of the bill, let me lay out where I stand (absent this bill) on voting rights and the conduction of elections.

To kick this off, I should note that I’ve been building and running voting and election systems in some form or other going back as far as 1999. As a young ‘un, I was Des Moines High School’s delegate to New Mexico’s Boys State summer program. (It was at this same program where I got to be very rude to a future presidential candidate and made up for my youthful indiscretion by voting for him years later.) As part of Boys State, attendees were assigned to parties upon arriving and the week was structured around building a party apparatus that would push candidates that would produce a functional government for our own State of New Mexico. The year that I attended, this was all done on paper, and could be a lengthy process.

When I went to college, I kept up with the organizers of the conference and sold them on the idea of an electronic voting system when I was already doing software consulting as a college freshman at Princeton. During my freshman year, I created a web-based PHP system that would allow for computer-based voting and I deployed it to 1999’s summer Boys State cohort. The system worked in that we successfully conduced the elections online (including one accident where I deleted the database and had to reconstruct it by translating logging statements into SQL commands to restore it).

After the Boys State experience, I was student in game theorist Timothy Feddersen’s online democracy course that he taught as a visiting professor at Princeton. As part of the course, we did all of our deliberations and voting online with a constellation of services cobbled together by the University’s local IT department. My final paper for that course was a critique of the system we used, and Feddersen approached me about joining a startup he was forming with a fellow Kellogg partner, Daniel Diermeier (now Chancellor of Vanderbilt University). The company was called ElectionWare, and I built the bulk of the system while in St. Petersburg (the Russian one) during the summer of 2000 (to ostensibly learn the local language) and during my junior fall semester at Princeton. We piloted the system in the spring of 2001 at Northwestern University, where Feddersen had returned and was running the online democracy course with Kellogg business students. As my own research at Princeton was ramping up (the earliest progenitor of the context-aware systems I’m still building), I sold my stake in the software and the company back to Diermeier and Feddersen, who continued to develop the system at Northwestern University’s Academic Technologies. John Norstad and Phil Burns took over the project and ended up rewriting the system - renamed AyeWare - which ended up becoming a research test bed for experimental manipulation of online community dynamics after the first Dot Com bubble popped. It was that software that got my foot in the door at Northwestern University as my first full-time job as a software developer, so in a small way, I can credit computerized election systems as a reason for having a career in the first place.

While I haven’t been involved in writing electronic voting systems for the better part of two decades, I have served on the operations side of things as one of my local precinct’s election judges. As part of that training, I now have several years of experience with running elections outside of educational and research contexts. To say that I have Thoughts on the Matter is a bit of an understatement.

Here are the principles that I firmly hold:

- Every eligible voter should have the opportunity to cast their votes, without political interference in the form of voter suppression, artificial hurdles, and any other obstacles that impedes their ability to cast a ballot. I unequivocally reject the notion that voting should be difficult so that only people who are motivated exercise that basic right.

- Voting must be secure in order for anyone to have any faith in the outcome of elections. Security must be realized at the time of voting (e.g. not allowing someone to masquerade as someone else and vote in their place, not creating opportunities for changing tallies, etc.) as well as after voting (e.g. multiple auditable paper trails, physical security of machines, memory cards, and paper artifacts, etc.). People should be able to hold the reasonable expectation that their voting is secure, and also hold the reasonable expectation that should there be shenanigans, we have the physical means (paper trails) to detect where the issue occurred and address it.

- In order to achieve the most representative government possible, we have a collective social interest in encouraging voters to exercise their basic rights, and should enact policies to maximize turnout among eligible voters.

- Election systems should be responsible for notifying the voter about the status of their ballot, from issuance to tabulation. This is a solved problem in traditional physical locations, and it should be solved in alternative (mail-in) and emerging contexts as well.

- Election systems should be managed and administered as locally as possible to firewall any bad behavior from one precinct spilling into another. As Trump’s badgering of the GA (and other states) voting folks demonstrated, candidates (esp. incumbents) will be incentivized to “play the refs”, so I want control to be as transparent and distributed among local officials as possible to make that undertaking (influencing election officials) as difficult to pull off as possible.

As someone who built voting systems in the past, I don’t have any hard preferences about the systems or forms that voting takes, as long as the principles above are respected and the people responsible for the processes/technology are competent. (Patch your systems, people!)

So, with that said, how does H.R.1 stack up? Here’s what I like (pulled from the Vox explainer):

- Automatic voter registration and online registration updates? I like that. However, rather than this being a national system, this should be delegated to the states with federal funding to help cash-strapped states get this up and running.

- Reduce Federal Election Commission from six to five? I like that. I’d also go a step further and mandate that the Commission must have alternates appointed for immediate elevation or some other mechanism for avoiding unfilled seats as we experienced during the Trump administration, rendering the commission completely useless.

- Restoring voting rights to felons who served their sentence. This should be consistent across states for federal elections, and unless we’re going to stop taxing felons, we shouldn’t take away their representation, either. Furthermore, this shuts off a potential avenue of seeking to turn inconvenient voting blocs into communities of felons as a way of keeping them from the ballot box.

- Mandatory independent redistricting commissions. While I support this idea in general, I waffled on it a bit as a federal mandate that states must implement (for federal elections). My main hesitancy is wondering if state parties won’t find ways to render the “independent” nominal and come up with other partisan ways of manipulating districts. If it’s not already in the bill, I would go a step further and mandate some additional mathematical standards to constrain the folks drawing the districts.

- Making Election Day a federal bank holiday. While I’m not sure whether this currently remains in the bill or not, I’m a big fan of giving people time off of work to go out and vote and help others vote. We could expand voting locations dramatically if local election officials didn’t limit their pool of potential volunteers to folks willing/able to take Tuesday off of work.

Here’s what I don’t support (in this bill):

- Campaign finance and ethics reforms. While I support most of the proposed reforms on their own, a voting rights bill isn’t the right place for these. I’d rather split these out into their own bills and force up-and-down votes on these individually, rather than have something in one of them (such as the public financing of elections) take down the voting improvements with it.

- Use of non-returnable returned mail to purge voters from rolls. Do you know those voter cards you get in the mail months before an election? And how you can show them to poll workers? I have a sad truth for you - poll workers don’t care about those cards. The purpose that they serve is to establish whether you still live at the location where you’re registered to vote. If you receive the card, then the local election authority knows you likely still live at your address. If it’s returned undeliverable to the election authority, then you are either purged from the roll or (in the state of Illinois at least) you will have to show proof of residency in order to vote. This is a nifty mechanism that I’m not willing to throw away, unless a substitute system is provided, such as a federal database - that states update - to indicate where voters are registered.

And where I’m still making up my mind:

- Mandatory early voting for 15 days and unrestricted mail-in voting. I’m still wrapping my head around this one. While I enjoyed voting early this time, I still think it should be left up to the states and their voters to determine logistically what they’re willing to take on. If the Election Day national holiday remains part of the bill, this item gets put into my scratch-it bin. If the national holiday provision is stripped out, then it goes to my keep-it bin.

Overall, there’s quite a bit that I like in this bill, but I think it has severe structural issues in that it’s also trying to serve as a Trojan horse for campaign finance and ethics reforms (that I generally support as well). I think that these structural issues make the passage of the stuff that I do like less likely, and would prefer to see a cleaner bill focusing on voters split off and voted up-and-down on its own.

I’m also less concerned about the constitutionality of the bill than I was when it made it out of the House. While the role of States in managing elections was front-and-center earlier this year, Article 1, Section 4 grants Congress the final word:

The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators.

There may be some other constitutional issues lurking (especially in the campaign finance reforms and on imposing additional requirements for tax disclosures on presidential candidates), but from a plain reading, Congress is empowered to exercise its power here, as far as making election rules.

Finally, there’s an ongoing debate about the importance of this bill and whether Senate Democrats should attempt to reform or abolish the filibuster to get this legislation passed. I’m going to push pause on that debate and return to it in the future, should it become a bit less hypothetical than it is now and we have a sense of what the final bill ends up becoming. That said, if there’s an aspect of this 800-page bill that I’ve not addressed in broad strokes above (such as new curb-side voting standards), post a comment with it and I’d be happy to respond.

Book reports

I didn’t do too much traditional eyes-on-paper reading this week, but I did listen to a couple of audio books courtesy of expiring Audible credits. This has put me way behind on my podcasts, but way ahead on my gardening.

A Murder of Quality by John le Carré (★★★☆☆): When I jumped into the George Smiley books, I was expecting Cold War espionage action. While his first book Call for the Dead touched upon some of that, it was more a murder mystery than spy novel. This second book dispenses with the spy stuff altogether to have Smiley investigating a murder at a British prep school.

It’s not what I signed up for, but I listened through this novel, which was a sufficiently entertaining experience. While I’m a fan of the mystery structure where the clues are given to the reader up-front and the story’s about figuring out how they fit together (the classic Sherlock Holmes story), le Carré’s method is more of a point-of-view perspective of the protagonist and you’re largely along for the ride as they figure stuff out, often using context not available to the reader. It’s an okay journey, but not what I’m looking for when it comes to mysteries.

After this book, I looked ahead to synopses of the upcoming novels and it looks like those are getting back to espionage and intrigue, so I’m still along for the ride. However, reading these first tow books have been like the time I watched the first Friday the Thirteenth film to get a handle on the Jason Voorhees mythos. Just like the hockey-masked killer from that franchise, the spy stuff is pretty much absent from these early novels, contrary to popular expectation.

The Minuteman: The Forgotten Legacy of Nat Arno and the Fight Against Newark's Nazis by Greg Donahue (★★★★☆): This was a relatively quick listen (under 2 hours) that presented the fascinating history about how members of the Jewish mafia turned into an anti-Nazi gang during Nazism’s rise in New York and New Jersey in the 1930s before World War II broke out. An Audible exclusive, it’s a good bit of historical storytelling if you’re a subscriber to that service.

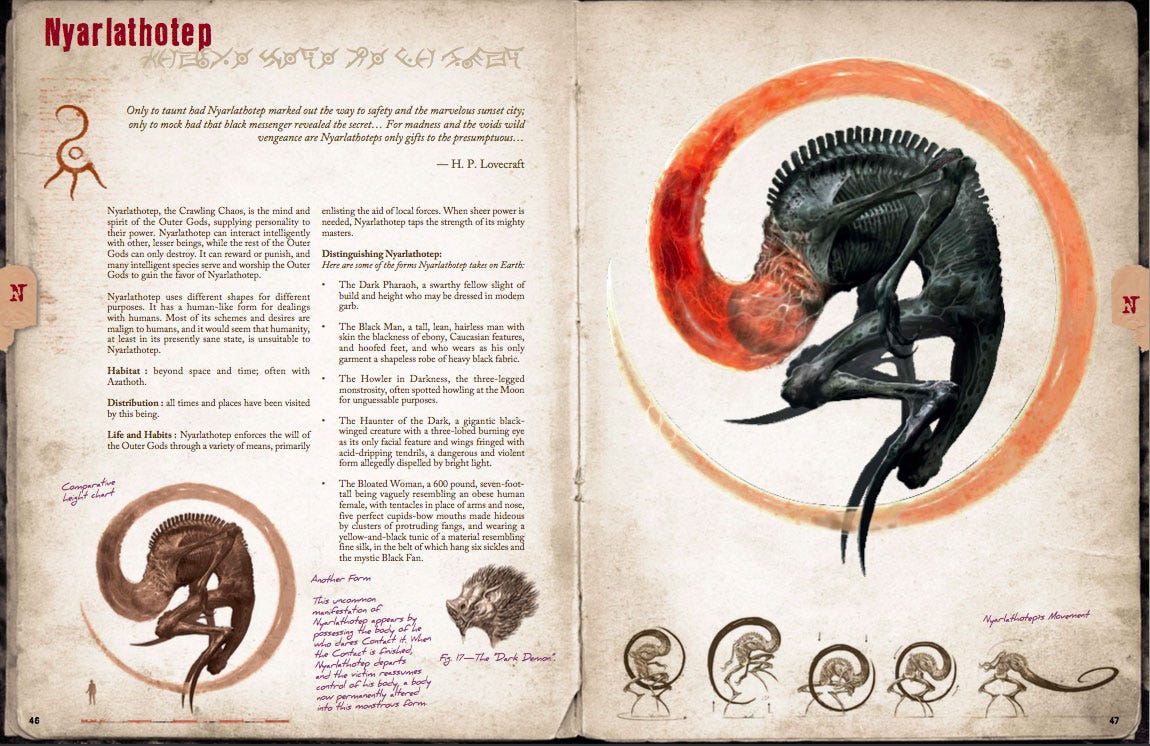

S. Petersen's Field Guide to Lovecraftian Horrors: A Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities and Beings from Beyond the Wall of Sleep by Sandy Petersen, Lynn Willis, and Mike Mason (★★★★☆): I picked up this book as a reference source for a project I’m working on and enjoyed the illustrations and descriptions of the creatures that Petersen pulls out of Lovecraft’s mythos for use in RPG settings. Not much else to say other than it’s quite pretty and I’ll be cracking it open quite a bit in the months ahead.

Interesting reads and watches

WallStreetBets donates more than $350,000 to gorilla charity to prove ‘apes together strong’ (The Verge)

Krispy Kreme will give you a free doughnut every day this year — if you've been vaccinated (CBS News)

The Magician's Library (Walter Kirn)

I’ve been spending most of my space time this last week in the Star Trek universe, having made it through the second season of Star Trek: Discovery earlier in the week.

Be careful accepting gifts from angelic time travelers, CMDRs!